Research that Demystifies the Controversial Topic of Shaken Baby Syndrome

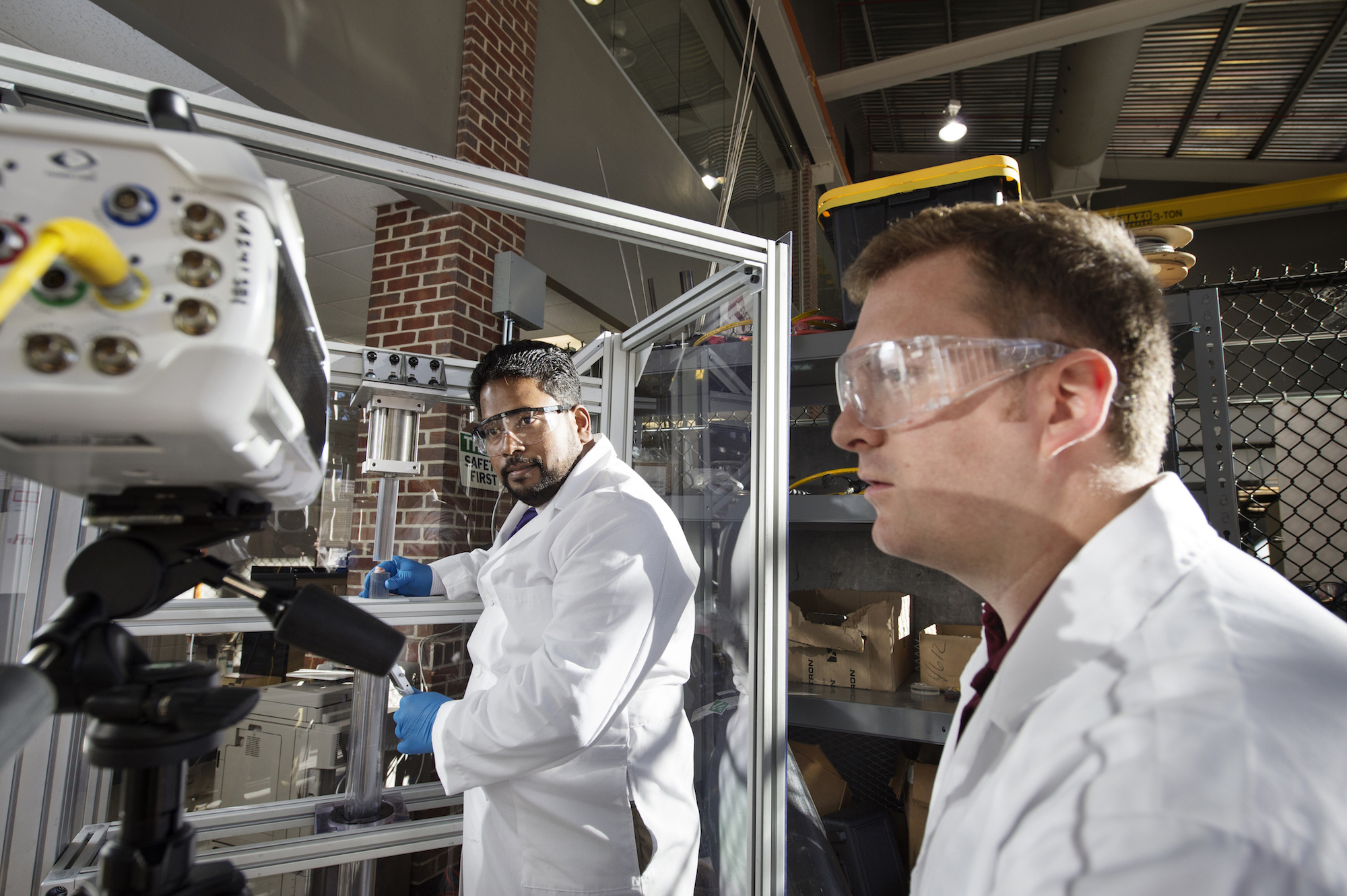

CAVS research on Shaken Baby Syndrome: Wil Whittington (assistant professor of mechanical engineering) and Raj Prabhu (assistant professor of biological engineering) use the Serpentine Intermediate Bar to study potential brain damage, using tissue from a surrogate pig brain.

(photo by Megan Bean / © Mississippi State University)

An international partnership between CAVS and Cardiff University is seeking to redefine the world’s understanding of the decade’s long controversial topic, shaken baby syndrome.

Raj Prabhu, assistant professor of biological engineering at Mississippi State University and Wilburn Whittington, assistant professor of mechanical engineering, explains that proper testing of SBS is based on results that do not account for the full biomechanics of a baby’s head trauma. In other words, the tests include a small handful of accurate measures that fail to contain the overall composition of the baby and the environment of the incident.

CAVS and Cardiff University (United Kingdom) researchers aim to change this problem by combining their different methods of research to enlighten the scientific and legal communities with never-before-seen data. Prabhu and Whittington have been working on a novel experimental device that will measure what they call intermediate strain rates. By using this device along with a surrogate pig brain (which has much of the same mechanical properties of the human brain) and supercomputer models, CAVS can test what happens to a baby’s brain when medium forces of movement are applied.

Whittington explains the frightening lack of data in this field of study.

“Well here is how scary it is, whenever you throw the baby up and the head moves, there is no data in the world that has ever been recorded that any scientist anywhere in any drawer or any paper in the history of mankind that can tell you what is going on at all. No one even knows. There is no person in this world that you can call up and even knows what is going on.”

A quote from a forensic pathologist and former chief medical examiner of Kentucky, George Nichols states, “Doctors, myself included, have accepted as true an unproven theory [SBS] about a potential cause of brain injury in children. My greatest worry is that I have deprived someone of justice because I have been overtly biased or just mistaken.”

Dr. Mike Jones, a leading expert on infant head trauma with Cardiff University in the United Kingdom explains, “Lack of thorough data have made shaken baby syndrome one of the most controversial topics in modern history, especially in the judicial arena. An exhaustive study was done by The Washington Post which reviewed murder and abuse cases involving shaken babies since 2001. Of the 1800 resolved cases, 200 of these across 47 states had charges dropped or dismissed; defendants were found not guilty or convictions were overturned. Much of this happens as doctors now revise their opinions on SBS.”

The data that is used now in the judicial system for crime scene investigations, for companies to design infant safety equipment, and for the government to set safety standards are collected from only a few infant post-mortem subjects. The issue is that it looks at the average response of the infant head trauma from a limited view that excludes particular injuries to the brain. Yet, what Prabhu and Whittington have discovered through data collected from the innovative device called the Polymeric Serpentine Bar, and through computer simulations, is that local injuries to an infant’s brain are vastly different from the average response and impact of trauma on an infant’s head.

According to Prabhu, “The issue of infant head traumas is that babies don’t get shaken at the rate of a blast wave. The impact rates are much lower, and it isn’t at a rate that is slow and methodical like a surgeon performing a surgical procedure, it is at a rate somewhere in between, and we call it intermediate strain rates.”

Again, on the Cardiff University side, one of Dr. Michael Jones’ key collaborators from the University of Leicester, Dr. Roger Malcomson, is one of the few in the entire UK who is a pediatric forensic pathologist. Malcomson conducts autopsies on deceased toddlers thanks to a UK law which classifies any baby death as a legal case automatically. This allows him to study the brains of the deceased if the cause of death is head trauma.

In speaking about what this connection does for the overall research, Prabhu said, “So what he brings to the plate now is forensic pathology from a clinical side, so we are now able to speak directly to our researchers from the clinical arena, which is one of the primary efforts.”

Moreover Prabhu says, “We’re {Cardiff and Mississippi State} are maximizing the impact of our research because not only are we providing some of the most useful data in understanding how the human body responds during impacts that cause harm, but we’re also providing information on how you might protect the human, how you might design components and things around a human and then how you might prosecute whenever those things happen.”

The CAVS and Cardiff research team are already uniquely tied and dependent on one another in investigating SBS to find life-changing solutions. For instance, laws in the U.S. prevent researchers from having immediate and easy access to study baby’s brains with infant head trauma. On the other hand, our neighbors in the U.K., scientists, and investigators are unable to test their data because they don’t have access to the innovative device or an avenue to supercomputers and engineers with the experience to model the research in a computational environment.

The international partnership also transforms how university research projects could be funded in the future. In the U.K., The Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), which is the U.K.’s equivalent of the U.S. National Science Foundation, has fully funded financial resources for a Ph.D. student to conduct joint research on the same topic.

It’s a win, win situation that Prabhu and Whittington believe will not only yield useful data in understanding the human body but will also provide new ways in thinking about protecting it and may revolutionize how the legal system handles such cases.

by Diane Godwin